Asian Americans v.s. Affirmative Action

Breaking the status quo. Asian Americans must over-perform in academics to compete on an equal level with their peers. Harvard as well as other Ivy Leagues admitted to placing Asian Americans at a disadvantage to create diversity on campus.

December 21, 2020

I drummed my fingers against the desk, anxiety coursing through my veins. My eyes glazed over the information I needed to fill out, and I paused at the race section. I read over the options in my head, and I stopped at the “Asian, including Filipino” bubble. I pondered over whether I should bubble in “Mixed” as my race as I am also of European descent. If I scored average on the test, it wouldn’t be considered “average” for an Asian American student. Universities would undermine my efforts all because of how I appear on the outside––my narrow eyes, my tan skin, my wide nose––I need to accomplish more to get into a school than other applicants.

Cornell University defines affirmative action as “A set of procedures designed to eliminate unlawful discrimination among applicants, remedy the results of such prior discrimination, and prevent such discrimination in the future.” However, as a 16-year-old Filipino-American, I have to wonder whether affirmative action eliminates discrimination or if it actually emphasizes what it’s trying to erase.

But how did we as a society get here in the first place? In 1961, President John F. Kennedy coined the phrase “affirmative action” to combat inequality and discrimination of the time. In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and pushed for the practice of affirmative action to ensure the equality of all American citizens. Over the years, the programs were a noble effort to help bring voices to those the system would have silenced because of the color of their skin. However, in 2020, affirmative action is an outdated practice that many colleges and universities still enforce today.

But how do colleges and universities use affirmative action? To boil it down, college admissions take into account the applicants’ race, ethnicity, religion, gender, or sexual orientation in the selection process and grant preference to those who belong in groups that the United States historically discriminated against.

However, instead of supporting and building up marginalized communities, it makes race a determining factor of whether or not an applicant gets into the college. And there’s one minority group that receives the worst end of it all: the Asian community.

Asian Americans v.s. Ivy League schools

A common trend in the U.S. education system is the success of Asian American students in comparison to other racial groups. As of 2018, the average SAT score of an Asian American student was 1223, 100 points more than White American students and over 230 more points than Hispanic and Black American students. For the ACT, the average score of an Asian American student is 24.5, 2 points greater than the average White American score, 6 points greater than the average Hispanic score, and 8 points greater than the average Black American score.

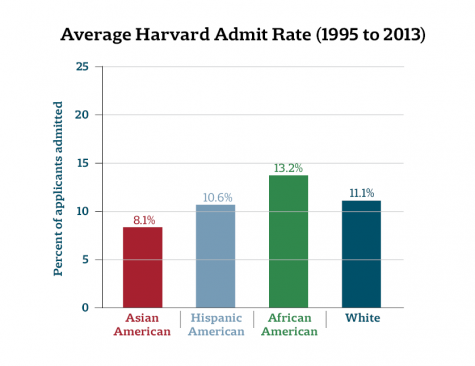

However, the accomplishments of Asian American students work against their favor. Asian American applicants saw the lowest acceptance rate of any racial group between the years of 1995 to 2013, despite the fact that Asian American students consistently outperformed in standardized tests compared to other racial groups. Moreover, in the 2014 Harvard lawsuit, the Dean of Admissions, William Fitzsimmons, admitted to sending recruitment letters to Black American, Native American, and Hispanic students if they scored at least a 1100 on the SAT. Unfortunately, Asian American students had to score at least a 1350 for females and a 1380 for males to receive a recruitment letter.

Additionally, in a 1990 investigation on Harvard admissions, it revealed concerning excerpts on comments made on Asian American applications.

One comment read: “Scores and application seem so typical of other Asian applications I’ve read: extraordinarily gifted in math with the opposite extreme in English.”

But aside from academics, Asian Americans excel in extracurricular activities as well. Unfortunately, however, Asian Americans participate in similar extracurricular activities such as piano and robotics, and it causes their applications to suffer amidst other applicants. The lack of diversity in their after-school activities showed “negative effects” on their chances of getting into Harvard.

Furthermore, the lawsuit also revealed that Harvard rated Asian American applicants lower than other ethnicities on personality traits such as “positive” and “widely respected”. This is according to the analysis of more than 160,000 student records.

Fitzsimmons claimed that they do this to “break the cycle” of minorities being underrepresented in Ivy League schools. Because of this, Asian Americans are no longer considered as “people of color” (POC) in the U.S. because they seem to thrive in school systems throughout the country. In fact, in 2016, the average Asian household received the highest income compared to the other racial groups in America.

Another example of this took place within the North Thurston Public School System in Washington. They recently grouped together White American and Asian American students and listed the other racial groups as “students of color” in their latest equity report. The school system defended themselves, stressing that “it shows that currently our Asian and White students are showing continuous growth while our system is not meeting the instructional needs of our Black, Indigenous, Multi-racial, Pacific Islander and Latinx students.”

California’s Proposition 209 dismantled affirmative action practices within public employment, contracting, or education. However, Proposition 16 challenged the idea of Proposition 209, stating that race, ethnicity, and gender should be taken into account. On November 3rd, voters rejected Proposition 16, continuing the race-neutral practices in their systems. Due to this, Asian American students are vastly overrepresented in UC schools throughout the state. In 2019, Asian American students make up 30% of the UC population, 6% more than White American students, 8% more than Hispanic students, and 26% more than Black Americans.

In spite of all this, many people still support the idea of affirmative action because they believe that the programs will diversify schools and represent the underrepresented communities.

The effects of “Mismatch”

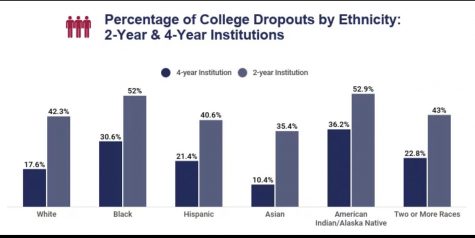

But does affirmative action really benefit minority students? “Mismatch” is the term used to describe when a student is over or underqualified for the university they are accepted into. And because of affirmative action, many minorities find themselves at universities they are unprepared for because of schools’ low standards for minority students. In 2019, 30.6% of Black American students dropped out of a four-year institution. The dropout rate was 21.4% for Hispanic students, 17.6% for White American students, and 10.4% for Asian American students. In Ivy League schools, the dropout trends among the racial groups remained the same. Although there are many other factors that contribute to these statistics, Mismatch is one of the main reasons why the minority dropout rate is so high. In fact, once California passed Proposition 209, the overall UC graduation rates increased by 4%. This means that students were able to complete college in schools based on their merit rather than their ethnic backgrounds.

Granting students admission into schools based on the color of their skin, ethnicity, or gender is unrealistic in 2020. In order to combat the oppression of the 1960s, affirmative action was necessary, if not crucial. But as the upper-middle-class consists of 2.5 million Black American men, it’s impossible to directly correlate income to a racial group. The same thing applies to Asian American income too as 11.1% of Asian Americans live at the poverty level. If anything, affirmative action should focus on the socioeconomic status of students, which is a more accurate representation of students who have fewer opportunities because of their low-income households. Not everyone can afford after-school programs and SAT prep classes, and it is imperative to take that into consideration when looking at standardized test scores. However, looking solely at the race of the student and making generic assumptions because of their skin color is not a beneficial form of measurement.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this piece belong solely to their respective author(s). They do not represent the opinions of South Forsyth High School or Forsyth County Schools.